Big Data, Big Change: The new AI Act has Big Implications for the Financial Services Sector

The European Parliament recently approved the EU’s proposed regulation on artificial intelligence (COM/2021/206), known as the Artificial Intelligence Act. The European Parliament recently published a corrigendum on its position on the Artificial Intelligence Act which corrects errors and clarifies the language of the Artificial Intelligence Act (the “AI Act”).1

The AI Act has general application and is not specifically aimed at financial services providers; however, it will have significant implications for how artificial intelligence (“AI”) systems are deployed in the financial sector. In this briefing, we examine:

- AI in the Financial Services Sector;

- the Role of the Regulator;

- classification of AI systems;

- overlap with the Capital Requirements Directive;

- penalties; and

- timeline for implementation.

AI in the Financial Services Sector

Financial services providers can leverage AI tools to:

- process anti-money laundering (“AML”) documentation;

- make credit assessments and risk assessments including risk differentiation (such as assigning criteria to grades or pools) and risk quantification (such as evaluating the risk of default). AI tools have the potential to generate liquidity models, haircut models, perform stress tests, forecast operational risk, evaluate collateral, and analysis markets. While managers and supervisors may be initially wary of such AI generated assessments, especially if the underlying economic rationale is unclear,2 these functions are expected to only improve over time and to generate competitive advantages;

- manage claims and complaints;

- prepare first drafts of documents, such as drafting prospectuses, marketing communications with customers or reports to be submitted to regulators, or translating text into different languages;

- gain insights into customers’ price elasticity of demand and likelihood to switch between competitors. AI systems might be able to generate more customised interest rates for individual customers. However algorithmic collusion between competing firms is prohibited;3

- advertise to customers. By drawing data from budgets which customers set for themselves on financial services apps, AI tools can provide information about when customers are more likely to save or spend which in turn can help financial service providers to decide when to promote overdraft services or investment advice services; and

- prevent fraud by drawing on the pattern-recognition capabilities of AI tools and by processing large amounts of data about a specific customer or groups of customers. RegTech solutions can also be used to detect scams, for example when remotely onboarding new customers.4

Firms must be careful that their use of AI tools does not create a risk of discrimination. As AI systems are only as accurate as their data inputs, AI tools may be subject to bias. AI algorithms might use proxies instead of factors directly related to insurance risks/pricing, suitability assessments or creditworthiness which could skew results.5 Accordingly it is important that businesses understand how AI technology works, avoid conflating correlation and causation, and retain appropriate human oversight of automated AI processes and AI decision-making. Staff will require additional training (for example with respect to statistical analysis and methodology) in order to effectively use AI tools.

The European Securities and Markets Authority (“ESMA”) notes that AI may create a risk of overreliance on third-party service providers which could also lead to commercial capture and dependency.6 Financial services providers should consider if their policies and procedures with respect to outsourcing and governance could be adapted to apply to new technologies such as AI.7

In addition to considering the AI Act, firms should update their risk policies and procedures regarding information and communication technology in order to comply with new obligations created by the Digital Operational Resilience Act (“DORA”) which takes effect on 27 January 20258 and review their data policies to comply with the upcoming Financial Data Access (“FiDA”)9 regulation.10

The Scope of the AI Act

The term “AI system” is defined in the AI Act as:

The AI Act also has a wide territorial scope and applies to:

- providers placing on the market (i.e. first movers making the AI system available) or putting into service (i.e. supplying for first use directly to the user or for own use) AI systems in the EU, irrespective of whether those providers are located or established within the EU or in a non-EU country;

- users of AI systems located or with establishments within the EU; and

- providers of AI systems that are located or with establishments in a non-EU country, where the output produced by the system is used in the EU;

- importers and distributors of AI systems;

- product manufacturers placing on the market or putting into service an AI system together with their product and under their own name or trademark;

- authorised representatives of providers, which are not established in the Union; and

- affected persons that are located in the Union.11

The AI Act defines a provider as:

The AI Act provides a transition period for certain AI systems which have been on the market prior to the relevant sections of the AI Act coming into force, and which have not been significantly altered since being placed on the market.12 This is highly relevant as many financial service providers and insurance undertakings have been using AI systems for some time.13 It may also partially address the concerns expressed by:

- the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (“EIOPA”) that the broad definition of AI systems in the AI Act could capture mathematical models such as Generalised Linear Models which are often used in the insurance sector;14 and

- the European Banking Authority (“EBA”) that AI tools used in internal ratings-based models and capital requirements calculation15 which are unlikely to harm natural persons’ access to financial services, could be captured by the scope of the AI Act.

The Role of the Regulator

While the European Commission has set up a new European AI Office16 to share expertise and promote consistency across EU Member States, the AI Act states:

Whilst it is possible to exercise right to derogate from this position, it is likely that the Central Bank of Ireland (“CBI”) will be tasked with market surveillance with respect to AI systems provided to or used by regulated and supervised financial institutions in Ireland (although note that the CBI will not be the designated competent authority for other sectors of the Irish economy to which the AI Act applies).The CBI will have to protect the confidentiality of the information provided to them such as intellectual property rights in AI systems.17

The CBI notes that:

and:

Financial services providers may be required to explain their decision-making processes and models to the CBI. This will be difficult for firms using AI solutions with a high degree of customisation or ‘black box’ technology.

Additionally, the CBI will need to develop new skills and expertise to effectively scrutinise AI tools and to avoid technology outpacing its ability to effectively regulate the provision of financial services.

Classification of AI systems

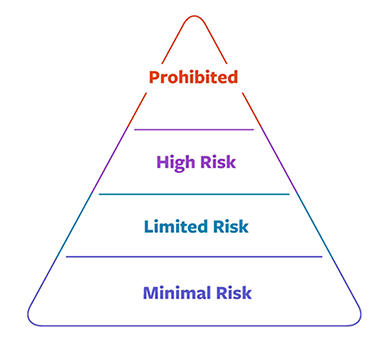

The AI Act regulates AI systems based on their intended use and the risks posed. The AI Act follows a risk-based approach, differentiating between uses of AI that create (i) minimal risk, such as spam filters, which are outside of the scope of the AI Act (ii) limited risk, which are primarily subject to transparency obligations (iii) high-risk, which are subject to the majority of the obligations or (iv) an unacceptable risk i.e. prohibited practices.

Limited Risk AI Systems

Where an AI system is not prohibited, and does not fall within the definition of a high risk AI system, the AI Act will primarily be relevant in the event that the AI system or its output is used by natural persons. Providers and deployers of these systems will be required to comply with transparency obligations such as ensuring that it is clear to natural persons when they are interacting with an AI system, unless it is obvious from context. There are also requirements in relation to watermarking of content and the disclosure of the use of “deep fakes”.

Given the very broad definition of AI systems, we expect that most financial service providers and regulated entities will be users or providers of AI systems which fall into the limited or minimal risk category.

High-Risk AI Systems

Chapter III of the AI Act sets out activities which are considered to be high-risk. These include AI systems that assess creditworthiness, assist with risk-assessment, pricing, or during recruitment processes (e.g. CV-sorting software). However, it is worth noting that the latest draft of the AI Act introduced a derogation where an AI system will not be regarded as high-risk where it “does not pose a significant risk of harm to the health, safety or fundamental rights of natural persons, including by not materially influencing the outcome of decision making...”. We expect that financial services firms will be examining this derogation closely, given the requirements that apply when using high risk AI systems that we set out below.

In addition to the transparency obligations described above, high-risk AI systems must comply with mandatory requirements with respect to:

- risk management (for example, analysing known and the reasonably foreseeable risks);

- quality management (which should be documented in the form of written policies and procedures and proportionate to the size of the organisation);

- conformity assessments;

- data governance;

- drawing up technical documentation (including descriptions of the design and logic of algorithms);

- records-keeping (including keeping logs automatically generated by AI systems);

- transparency (including informing customers and notifying the CBI of AI systems being made available or put into service);

- human oversight;

- accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity; and

- complying with relevant conformity assessment procedures.

Providers of high-risk AI systems should ensure compliance with the AI Act, draw up a machine readable, physical or electronically signed EU declaration of conformity with the AI Act (and update this declaration as appropriate), affix a CE marking to high-risk AI systems to show compliance with the AI Act, and register high-risk AI systems in an EU database. If high-risk AI might present a risk to human persons, providers should take corrective action and notify the relevant authorities.

Providers of black box algorithms that fall under the scope of high-risk AI systems will also have to comply with the mandatory requirements listed above, which may require developing methods and tools to explain the logic and reasoning of the algorithms, as well as the sources and relevance of the data used, in a clear and accessible manner. Firms may also decide to invest in supplementary explainability tools which help to understand how AI systems function.20 In addition to regulatory requirements, firms also need to be able to explain their decision-making in order to defend their decisions if customers challenge their decisions when exercising their right to redress through arbitration or litigation.

Article 82 of the AI Act enables the relevant authority of a Member State to find that although an AI system complies with the AI Act, it still presents a risk to the health or safety of persons and therefore the provider, importer or distributor of the AI may be required to take all appropriate measures to mitigate or remove this risk, to withdraw the AI system from the market, or to recall it within a reasonable period. Corrective measures must be taken without undue delay.

By providing more accurate credit-worthiness assessments, AI can mitigate the risk of over-indebtedness which is not in the interests of consumers or the financial system.21 The EBA suggests (with respect to an earlier draft of the Act) that, while statistical bias should be avoided, the Act should distinguish more clearly between bias and simply differentiating customers on the basis of their individual credit risk.22

Whether the European Commission considers additional exemptions for small-scale providers or exemptions for AI used solely by corporate entities when it reports on the AI Act four years after it enters into force, remains to be seen.

Note that the AI Act requires Member States to minimise the “administrative burdens and compliance costs for micro- and small enterprises within the meaning of Recommendation 2003/361/EC.” In light of earlier drafts of the AI Act, this could involve:

- giving small-scale providers priority access to AI regulatory sandboxes; and/or

- considering small-scale providers’ needs when setting fees or drafting codes of conduct.

It will be interesting to see whether the CBI establishes AI regulatory sandboxes to enable AI innovation, and how many market players avail of such opportunities.

AI Systems with an unacceptable level of risk are prohibited

Article 5 of the AI Act introduces a list of prohibited AI practices including:

- certain manipulative AI practices with the objective, or the effect of materially distorting the behaviour of a person or a group of persons by appreciably impairing their ability to make an informed decision, thereby causing them to take a decision that they would not have otherwise taken in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person, another person or group of persons significant harm;

- AI systems that exploit any of the vulnerabilities of a person or a specific group of persons due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation in a manner which is reasonably likely to cause harm;

- AI systems which classify people based on social behaviour or personal characteristics which is likely to cause detrimental or unfavourable treatment of natural persons or groups;

- AI systems that make risk assessments of natural persons in order to assess or predict the risk of a natural person committing a criminal offence, based solely on the profiling of a natural person or on assessing their personality traits and characteristics;

- the placing on the market, the putting into service for this specific purpose, or the use of AI systems that create or expand facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage;

- the placing on the market, the putting into service for this specific purpose, or the use of biometric categorisation systems that categorise individually natural persons based on their biometric data to deduce or infer their race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life or sexual orientation; this prohibition does not cover any labelling or filtering of lawfully acquired biometric datasets, such as images, based on biometric data or categorizing of biometric data in the area of law enforcement;

- certain uses of real-time remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible (physical) spaces for law enforcement purposes, with certain exceptions;23 and/or

- AI systems which infer natural person’s emotions in workplaces or educational institutions, with certain exceptions for medial or safety reasons (including searching for missing or abducted persons).

These prohibited practices are unlikely to have applications in the financial services sector.

Overlap with the Capital Requirements Directive

The AI Act states that providers of high-risk AI systems which are subject to quality management systems under:

An earlier draft of the AI Act referred to limited derogations from the AI Act in relation to the quality management system for credit institutions regulated by Directive 2013/36/EU (i.e. the Capital Requirements Directive). Therefore the CBI, if designated, will take a financial service provider’s systems under the Capital Requirements Directive into account when considering if it has quality management systems under the AI Act.

Additionally, Article 74(7) of the AI Act states:

Penalties

The AI Act sets out penalties for non-compliance with the articles concerning prohibited AI practices. Fines of up to a €35 million or 7% of annual turnover (which ever is greater) may be imposed by the courts for prohibited AI practices. Other breaches of the AI Act can attract fines of up to €15 million or 3% of annual turnover (whichever is greater). Note that these are the fines are separate to any cause of action which an individual might have, for example if an AI system discriminated against a candidate in a recruitment process.

The level of fine imposed will depend on:

- the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement and of its consequences;

- whether administrative fines have been already applied by other market surveillance authorities to the same operator for the same infringement;

- whether administrative fines have already been applied by other authorities to the same operator for infringements of other EU or national law, when such infringements result from the same activity or omission constituting a relevant infringement of the AI Act; and

- the size, annual turnover and market share of the operator committing the infringement.

These fines are comparable to other regimes that have been implemented by the EU in relation to its digital reform package. By way of comparison, the maximum administrative fine that can be imposed by the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) is “20 000 000 EUR, or in the case of an undertaking, up to 4 % of the total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher”.24 Penalties based on turnover are significant. For example, in September 2023, TikTok was fined €345 million by the Data Protection Commission.25

If the AI Act is designated as a designated enactment under Schedule 2 of the Central Bank Act 1942, then the CBI could, per its Administrative Sanctions Procedure (“ASP”):26

- investigate alleged breaches of the AI Act;

- reprimand a firm for breaching the AI Act;

- direct a firm to cease committing a contravention of the AI Act;

- impose sanctions for breaches of the AI Act, capped at the same level of the fines set out in the AI Act (rather than the courts imposing the relevant fine);27 and/or

- suspend or revoke a financial service provider’s authorisation. This can have significant implications for a firm’s business model, especially if it relies on a CBI authorisation to passport into other states in the European Economic Area.

Timeline for implementation

The AI Act will enter into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union (“OJ”), with most provisions applying 24 months after its entry into force. However, prohibitions (discussed above) will apply six months after entry into force, and regulations in relation to new general purpose AI systems will apply 12 months after entry into force. Certain product specific obligations come into effect after 36 months. The AI Act also implements grandfathering provisions in relation to certain existing AI systems, which makes the overall timeline for the application of the AI Act a complex picture.

The European Council is expected to formally endorse the AI Act in mid-2024. It is anticipated that the AI Act will be published in the OJ in Q2/3 of 2024 and accordingly, it is expected that it will substantially come into force in Q2/3 of 2026.

Conclusion

Financial services providers in Ireland will need to assess whether which risk classification applies to their AI systems. We expect that, while most AI systems in the financial services sector will be low risk, AI systems which provide creditworthiness or risk assessments and AI tools which influence pricing will fall into the high-risk category.

Also contributed to by Eunice Collins

- See here.

- See here.

- Put simply, anti-competitive coordination among competing firms that is facilitated via AI, even unintentionally, could be considered to be tacit collusion and therefore a breach of EU competition law.

- See here.

- See here.

- See here.

- Article 41 (1) of Solvency II Directive requires “insurance and reinsurance undertakings to have in place an effective system of governance which provides for sound and prudent management of the business.”

- DORA provides an oversight framework for third-party service providers of information and communications technology. For more information see our briefing on DORA here.

- See here.

- FIDA promotes open and data driven finance and gives customers greater flexibility when consenting to share their financial data with third parties by requiring data to be made available without undue delay. For example, consumers could access information about their insurance products from different providers on a single platform which could enable consumers to make more informed choices. See here.

- Article 2 of the AI Act.

- Article 111(2) of the AI Act.

- Note that the use of AI in the financial services sector reportedly increased during the Covid-19 pandemic; see here ; and here.

- See here.

- See here.

- See here.

- Article 78 of the AI Act.

- See here.

- See here.

- See here.

- See here.

- See here.

- While financial service providers may use biometric data for client authentication, this is not for law enforcement purposes and is not prohibited by the AI Act.

- Article 83(5) and (6) of GDPR.

- See here.

- The CBI published Guidelines regarding the ASP in December 2023 see here.

- The CBI published Guidelines regarding the ASP in December 2023 see here.

This document has been prepared by McCann FitzGerald LLP for general guidance only and should not be regarded as a substitute for professional advice. Such advice should always be taken before acting on any of the matters discussed.

Select how you would like to share using the options below